Schedule

Team Canada (Men)

IIHF World Junior Championship | Dec. 26, 2024-Jan. 5, 2025

Spengler Cup | Dec. 26-31, 2024

4 Nations Face-Off | Feb 12-20, 2025

IIHF U18 World Championship | April 23-May 3, 2025

IIHF World Championship | May 9-25, 2025

U17 World Challenge | Nov. 3-9, 2024

Hlinka Gretzky Cup | Aug. 5-10, 2024

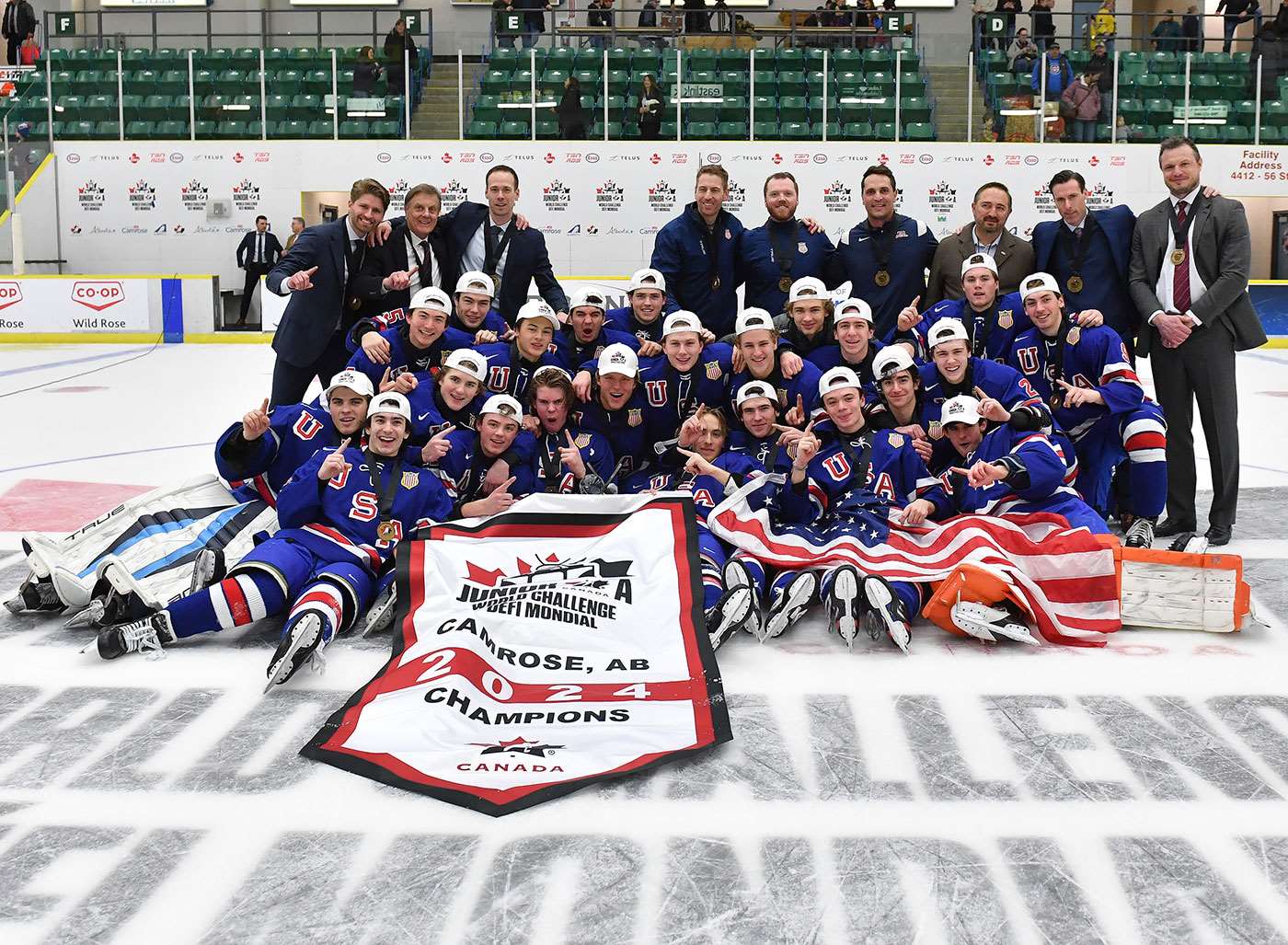

Junior A World Challenge | Dec. 9-15, 2024

National Junior Team vs. USPORTS | Dec 12-13, 2024

Search

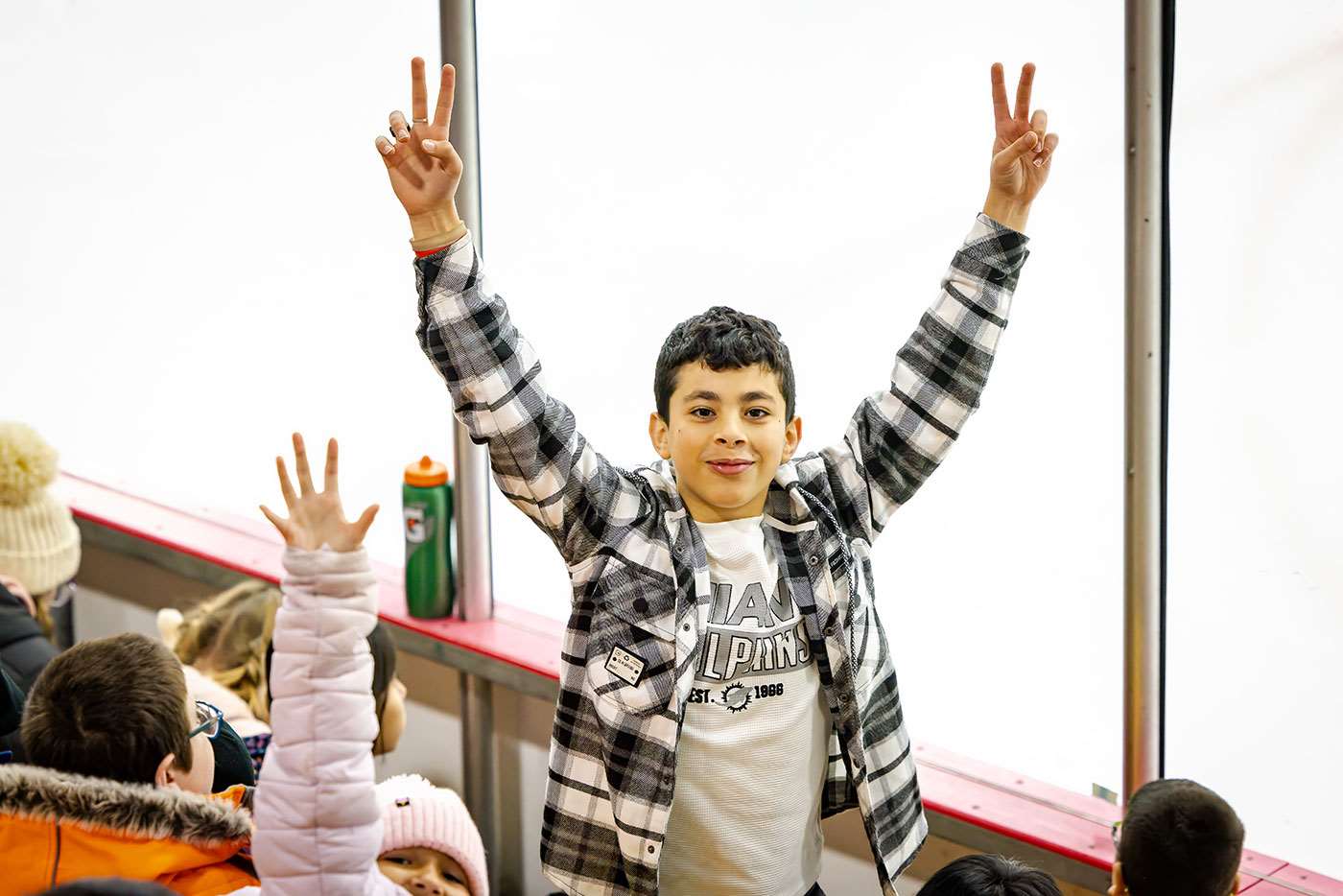

Giving back to the game

Canada’s National Women’s Team alumnae continue to grow their sport

When Carla MacLeod walked into Fisht Olympic Stadium in Sochi, it wasn’t the first time she marched into the Opening Ceremony at an Olympic Winter Games behind a red-and-white flag. This time, though, it wasn’t a red maple leaf in front of the 2006 and 2010 gold medallist; it was the red circle of the sun.

For the past two years, MacLeod has been an assistant coach with Japan’s national women’s team.

She is just one National Women’s Team alumna in Sochi who’s committed to growing the women’s game.

Cassie Campbell-Pascall and Jennifer Botterill can both be found behind the microphone for CBC, more visible roles than their usual dedicated work behind the scenes promoting and developing women’s hockey.

After Japan failed to qualify for the 2010 Games, the team approached Hockey Canada for help in finding a female coach who had played the game. Melody Davidson, general manager of the National Women’s Team programs, suggested MacLeod, who was – and still is – a coach at Mount Royal University in Calgary.

“I liked the challenge this position posed,” says MacLeod. “I felt like the players were this incredible blank canvas and I had some of the best paints in the world to make a great piece of art.”

Coaching teams on both sides of the pond means MacLeod spends up to 10 days a month in Japan – “I’ll be honest, half the time I don’t know up from down” – but it gives her a satisfying feeling that she is helping grow the game way she loves.

“Because the sport is so young, it’s critical to give back and try to help these nations develop the game,” she says. “This sport deserves to be an Olympic sport, and we’re working hard to ensure it stays one.”

Botterill is between the benches during games and interviewing players and coaches during intermissions and after the final horn. Recently the three-time Olympic champion acted as an athlete ambassador to the Russian team as part of the IIHF Ambassador and Mentor Program, an initiative launched in 2011 that paired coaches and players from the elite women’s programs with teams in countries that are still growing the game.

Botterill met with the team in Calgary, offered feedback to coaches in follow-up calls and communicated with players via email and social media.

A good showing in Sochi would go a long way to building the game in a country already obsessed with men’s hockey. “It would really help the growth of the sport in the country,” she says. “The crowds have been tremendous for [the women’s] games already!”

While Botterill is rinkside at Shayba Arena, Campbell-Pascall is in the booth calling games. As the only player to captain Canada to two Olympic gold medals, Campbell-Pascall is used to being one of the faces of women’s hockey. She retired from the national team in 2006, but as a broadcaster now has the chance to share other players’ stories.

She’s currently vice-chair of the board with the Canadian Women’s Hockey League, as well as a member of its sponsorship committee. Fourteen members of Canada’s National Women’s Team presently play in the CWHL, “a league that allows our best players a place to play after college,” she says, “and helps develop our coaches.”

Considering what hockey has given each of them, staying involved in the game has been a no-brainer for all three women.

“I earned my university degree on a [hockey] scholarship,” says MacLeod. “I’ve also learned the value of setting goals and working hard, and I think both are qualities that help in any situation in life.”

Botterill feels equally fortunately for what the game has allowed her. “It has given me the most incredible life experiences and taught me lessons I will use in so many different aspects of my life.”

“Hockey taught me how to be a strong individual and a lot about leadership,” says Campbell-Pascall. “It also gave me a husband, as I met him through hockey, and with that, my daughter.”

For other girls and women to enjoy these same experiences, more of them need the chance to be on the ice. There are fewer than 600 girls registered in hockey in Russia and only 2,500 in Japan. More than 87,000 girls are registered in Canada.

MacLeod says those responsible for Japanese hockey has made a concentrated effort to grow the game, securing knowledgeable coaches and running camps to get players reader for competition. “The sport isn’t popular in Japan, but with our team in Sochi, the media coverage has been incredible. Our participation and our ability to do well will have a tremendous impact on the game in Japan.”

These Games marked the first time the Japanese women’s program qualified for an Olympics; they played in 1998 as the host nation. Since then the game as a whole has grown leaps and bounds.

Like MacLeod, Campbell-Pascall credits nation’s governing bodies for investing more in their programs. “The game has become more competitive,” says Campbell-Pascall. “The players are faster and stronger than we were [in 1998].”

MacLeod agrees that today’s players skate with more speed and skill – and that excites her. “All you have to do is watch [Marie-Philip] Poulin or [Rebecca] Johnston shoot a puck and you’ll see improvement!” she says. “The game today is headed in the right direction.”

If the alumnae have their way, that direction will lead to a future that includes a women’s professional league.

“I would love to be sitting in my rocking chair one day and reading about women making a good living playing the game,” says MacLeod. And it’s a sport that’s well on its way to being more accepted worldwide, adds Campbell-Pascall.

“Not every girl has to play hockey,” says Botterill, “but I love that they have a choice to.”

For more information: |

- <

- >