Schedule

Team Canada (Men)

IIHF World Junior Championship | Dec. 26, 2024-Jan. 5, 2025

Spengler Cup | Dec. 26-31, 2024

4 Nations Face-Off | Feb 12-20, 2025

IIHF U18 World Championship | April 23-May 3, 2025

IIHF World Championship | May 9-25, 2025

U17 World Challenge | Nov. 3-9, 2024

Hlinka Gretzky Cup | Aug. 5-10, 2024

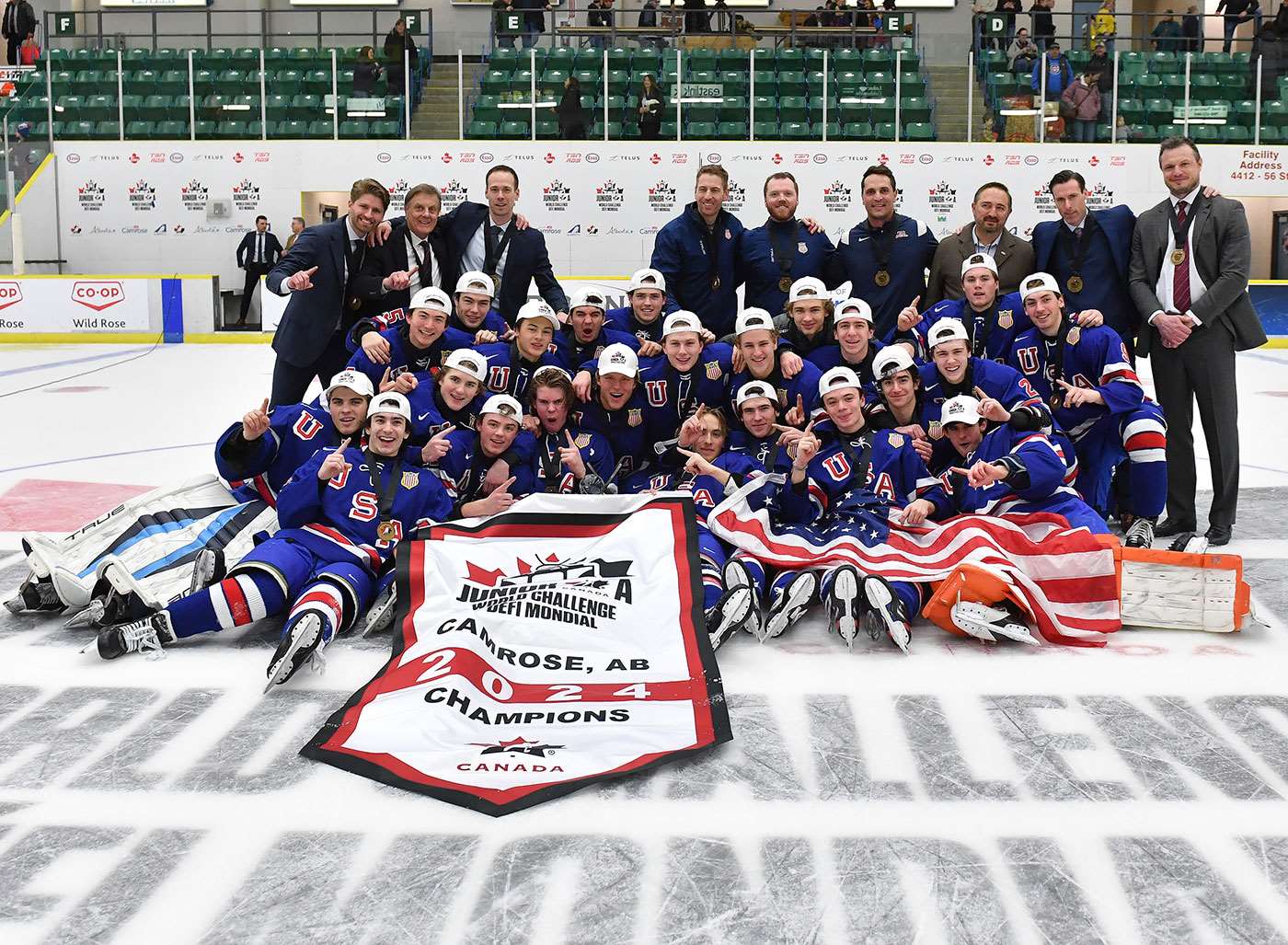

Junior A World Challenge | Dec. 9-15, 2024

National Junior Team vs. USPORTS | Dec 12-13, 2024

Search

Riley’s remarkable recovery

When Garrett Riley broke his leg at the end of October, many thought his season was over. But he didn’t.

The collision looked normal enough. But as the bodies cleared and the play moved on, Garrett Riley was still lying on his side in the neutral zone. Athletic therapist Michael Lenart was on the ice and over to Riley as soon as the whistle sounded. He immediately called for medical support. Within seconds, Dr. Roy Diklich was at Riley’s side and signalling for an ambulance.

Riley’s right leg – his only leg – was badly broken.

Riley is no stranger to hospitals. He was diagnosed with osteosarcoma at 15 and had his left knee replaced with a prosthetic joint to try and save the rest of his leg. Seven years later, an infection took hold and Riley became septic, leading to an above-knee amputation when he was 22. Since that operation in 2017, he has dealt with issues surrounding his residual limb, including extreme pain requiring a handful of additional surgeries.

Riley is no stranger to hospitals. He was diagnosed with osteosarcoma at 15 and had his left knee replaced with a prosthetic joint to try and save the rest of his leg. Seven years later, an infection took hold and Riley became septic, leading to an above-knee amputation when he was 22. Since that operation in 2017, he has dealt with issues surrounding his residual limb, including extreme pain requiring a handful of additional surgeries.

Things got so bad the rapidly rising young para hockey star had to step away from the game after the 2018-19 season, just a year into his national team career. The Brantford, Ont., native worried that might be the end of his hockey journey, but the pain wouldn’t relent.

“I’ve had three surgeries in the last two-and-a-half years on my residual limb to try and fix the pain that I have constantly, every day,” Riley explains. “And unfortunately, none of the surgeries have really worked so it was a big setback in my career.”

In August 2021, Riley had a further resection of his residual limb just weeks before Canada’s National Para Hockey Team selection camp. He was already feeling like an underdog going in, having been away from the program for two years, and physically wasn’t at his best. But head coach Ken Babey didn’t see it that way. He saw a young player with raw talent back in the fold. Babey was excited about the prospect.

We were hoping Garrett would show up at selection camp ready to play this season and he did,” Babey says. “He made the roster and was really starting to come along [early in the year].”

Coming out of camp, Riley felt good about the season. The first hurdle on the way to 2022 Paralympic Winter Games was cleared, training was going well and the season schedule was shaping up nicely, including an early season trip to St. Louis for a two-game series against the United States.

The trip started well, but busy. Two practices a day to open the week meant long days at the arena and spending time together as a team. There was also the curiosity of the rink itself – the games were going to be outdoors. But when the team arrived in St. Louis, the ice hadn’t even been started. Each and every day the team would arrive and check on the progress.

Everyone was surprised when the ice was ready for puck drop on Oct. 29, and the excitement was palpable. Fans started arriving, including a family of four originally from north of the border, all dressed proudly in the red and white. Riley was anxious to get back on the ice wearing the Maple Leaf, but all the nerves drifted away in warmup.

Everyone was surprised when the ice was ready for puck drop on Oct. 29, and the excitement was palpable. Fans started arriving, including a family of four originally from north of the border, all dressed proudly in the red and white. Riley was anxious to get back on the ice wearing the Maple Leaf, but all the nerves drifted away in warmup.

Canada’s game was physical from puck drop, which is hardly a surprise given this was the first meeting between these two rivals since the 2021 IPC World Para Hockey Championship gold medal game, where the Canadians did not walk away with the top prize. Riley wasn’t on that roster, but the whole team felt it was important to make its presence known early.

It was his second shift in the first period, just barely enough time into the game to work up a sweat. Riley was skating through the neutral zone when U.S. forward Brody Roybal headed for a loose puck. There was no way to beat the American there, so Riley planned to finish the check. As did Canadian defenceman Adam Dixon. Roybal saw Dixon coming and stopped short. Riley hit the boards straight on and stopped dead, just as Dixon’s sled hit him. No one knows how Riley’s leg came out of the strap, but it took the full force of the hit, breaking both the bones in his calf.

I remember I had my eyes closed when they were trying to get me out of my sled and onto the stretcher and I just remember someone grabbing my hand,” Riley recalls. “It was (equipment manager) A.J. Murley and I will always be grateful for him in that moment.”

Diklich rode with him in the ambulance to the hospital and spoke to the St. Louis care team. As an emergency room physician himself, Diklich has seen his fair share of bad breaks. He was there when they tried to remove Riley’s equipment but had to sedate the forward to do so. And once it was off, it was evident why. Riley had a compound fracture; the tibia had broken through the skin. A difficult injury for anyone to deal with, let someone with only one leg.

Diklich rode with him in the ambulance to the hospital and spoke to the St. Louis care team. As an emergency room physician himself, Diklich has seen his fair share of bad breaks. He was there when they tried to remove Riley’s equipment but had to sedate the forward to do so. And once it was off, it was evident why. Riley had a compound fracture; the tibia had broken through the skin. A difficult injury for anyone to deal with, let someone with only one leg.

Riley was in surgery within eight hours. He had a rod installed to support the tibia and was feeling strong enough to attempt walking the next day. That proved to be too much, and plans to get Riley home on a commercial flight were dropped. Team coordinator Mitchell Furlotte waited for a few days with Riley in St. Louis until a medical flight could be arranged.

But getting home wasn’t the hardest part of this journey. Riley’s injury happened just 127 days from the start of the Beijing Games. A typical recovery from a compound fracture is about two or three months, but that is a long time for a high-performance athlete, who trains six days a week in the gym or on the ice, to be out of action, especially in a Paralympic year. So, Riley decided right away not to be down that long and that his injury would not stop him from making the team, not after everything he had been through over the last two years.

"It was definitely in my mind at first that I was done for the season,” Riley says. “But then I just thought I was done with laying around not doing anything, so if something goes wrong it goes wrong, but at that point, I just needed to push myself and get back out there.”

Two weeks after the collision, Riley was back at the gym. Arm workouts only, but focused on keeping up everything he had gained over the year. He was in constant contact with team support staff and even worked with some trainers he knew from his Team Ontario experience. Grinding it out in the gym alone for over a month was hard on Riley, but he kept his mind on the goal and built a little each day.

Then an infection took hold.

It started off small enough, but for Riley even that brought back memories from his teenage cancer and the infection that ultimately cost him his left leg. It was a tense two weeks, with everyone in Riley’s life watching and waiting to see if he could fight it off. Suddenly, returning to hockey wasn’t the priority anymore. Saving his one remaining leg was all that mattered.

It started off small enough, but for Riley even that brought back memories from his teenage cancer and the infection that ultimately cost him his left leg. It was a tense two weeks, with everyone in Riley’s life watching and waiting to see if he could fight it off. Suddenly, returning to hockey wasn’t the priority anymore. Saving his one remaining leg was all that mattered.

I just kept doing things that I was in control of and able to do to help me get along and get to the point that I needed to be,” Riley says.

He rejoined the national team in Calgary in December for a training camp (which was in place of the cancelled Canadian Tire Para Hockey Cup), though he still wasn’t cleared to be on the ice. During practices, strength and conditioning coach Bryan Yu would bring a cardio machine rinkside so Riley could watch. For the first time in six weeks, he really felt like a part of the team.

But there was still the matter of getting him on the ice. The orthopedic doctor in Ontario took a much more conservative approach than Riley would have liked, but given the extent of the injury and the infection, there wasn’t much of a choice. Even with the protection of the sled, getting back into full training, especially contact, before the injury was sufficiently healed could have detrimental long-term effects. Plus, Riley still used his leg for balance while skating, which he noticed still caused pain when he was finally medically cleared to return to practice.

Two months to the day from the accident – Dec. 29 – Riley was back on the ice. It was a hub skate in Toronto with three other Ontario-based team members. He worked by himself for a while, getting comfortable in the sled and with his leg, before joining the rest of the players in drills. It was a great day and as word of his return spread through the team, so too did some added energy.

“Being a part of his journey to just getting in a sled, not even really thinking it meant he was going to be competitive again or positioning himself to make the team was pretty special,” says Lenart. “But the reality is he had missed a big chunk of training time, and at this level any time you miss is time that your teammates and competitors are getting that you’re not.”

Would there be enough time?

Riley quickly had the same realization; those two months recovering had played havoc with his fitness and timing. If he wanted a shot at the Paralympic roster, he was going to need more ice time, more specific training and more coaching, but options were limited at home in Ontario. Babey suggested Riley come to Calgary early in January to work with him and the Alberta-based players, but also to have focused sessions with Yu and the support staff.

Riley quickly had the same realization; those two months recovering had played havoc with his fitness and timing. If he wanted a shot at the Paralympic roster, he was going to need more ice time, more specific training and more coaching, but options were limited at home in Ontario. Babey suggested Riley come to Calgary early in January to work with him and the Alberta-based players, but also to have focused sessions with Yu and the support staff.

It was a big ask. The team was already planning a month-long centralization bubble leading into the Paralympics and this would add another three weeks away from home – over nine weeks away in total if Riley made the final roster. But that was the goal; for the past year Riley had thought of little else than wearing the Maple Leaf in Beijing. Three extra weeks was not going to deter him from trying everything he could to be at his best when the coaches made their calls in early February to name the roster.

Twenty players had been selected to Canada’s National Para Hockey Team in September, but only 17 would be going to the Games. Riley knew the odds were good, but that didn’t help his nerves on the day the call finally came.

“That Zoom call was really emotional,” Babey says. “The way he fought his way back, I think he earned a lot of respect from his fellow players, and I know from the coaching staff and support staff.”

In that moment, everything Riley had been through in his life was rewarded. Cancer, an amputation, chronic pain, surgery after surgery, a broken leg; it had all been leading to the point where he would have a chance to live out a childhood dream and represent his country.

Garrett Riley was a Paralympian.

Photo Credit: Angela Burger/Paralympic.ca

For more information: |

- <

- >

Beijing 2022 ties a bow on an accomplished career with Team Canada.

Westlake joined the para hockey program in 2003 and has played as a

goaltender, a defenceman and a forward. He won gold at his first Paralympic

Games in 2006 and has since won two more Paralympic medals: bronze in 2014

and silver in 2018.

Beijing 2022 ties a bow on an accomplished career with Team Canada.

Westlake joined the para hockey program in 2003 and has played as a

goaltender, a defenceman and a forward. He won gold at his first Paralympic

Games in 2006 and has since won two more Paralympic medals: bronze in 2014

and silver in 2018.