Schedule

Team Canada (Men)

IIHF World Junior Championship | Dec. 26, 2024-Jan. 5, 2025

Spengler Cup | Dec. 26-31, 2024

4 Nations Face-Off | Feb 12-20, 2025

IIHF U18 World Championship | April 23-May 3, 2025

IIHF World Championship | May 9-25, 2025

U17 World Challenge | Nov. 3-9, 2024

Hlinka Gretzky Cup | Aug. 5-10, 2024

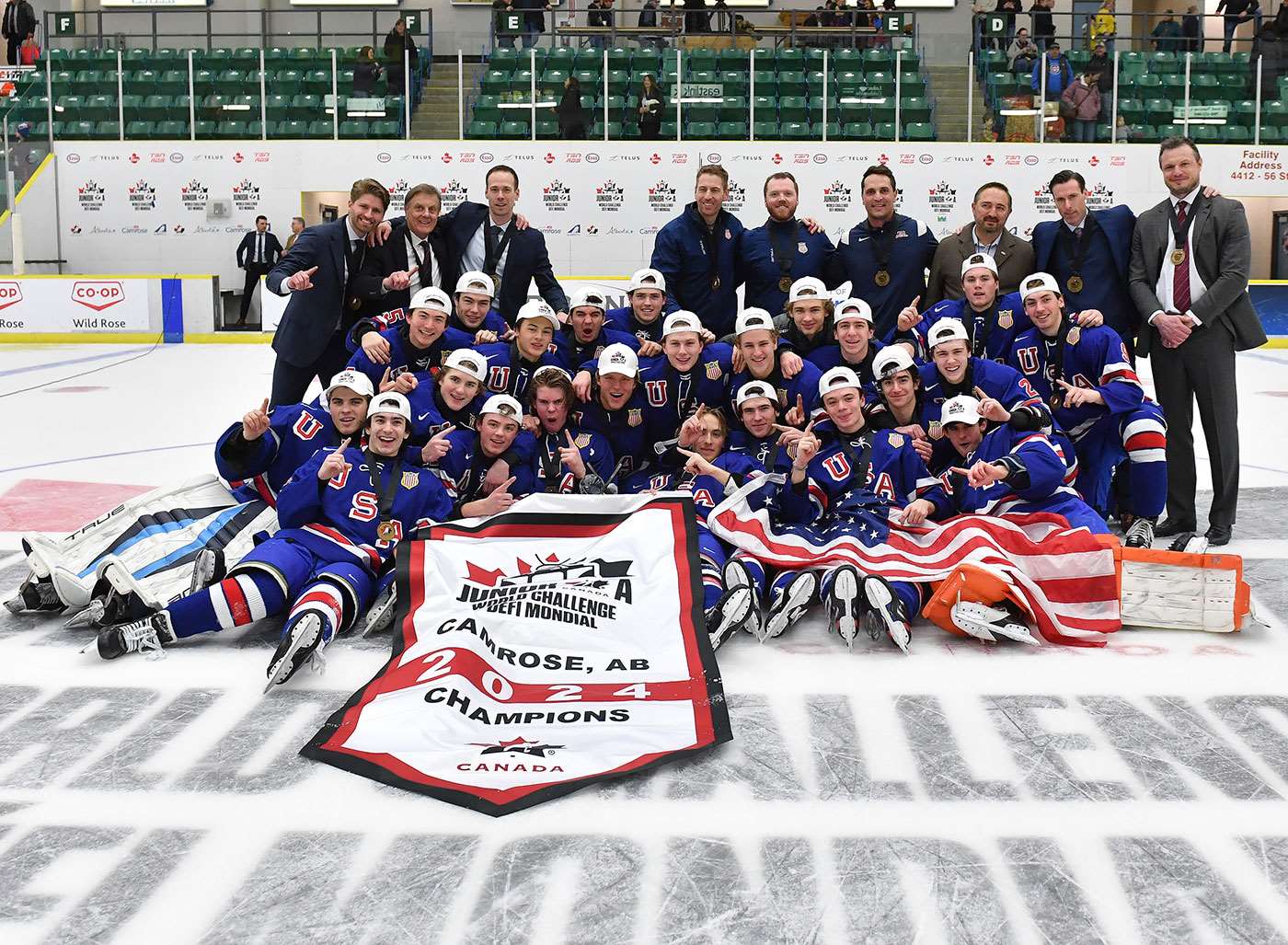

Junior A World Challenge | Dec. 9-15, 2024

National Junior Team vs. USPORTS | Dec 12-13, 2024

Search

The Long, Long Road to the RBC Cup

Winning a national championship means a lot of wins, and a lot of kilometres

In junior hockey there is really only one means of transportation to facilitate the travel required to complete a season: the bus.

Long personified as part of the team, the bus can come in different shapes, sizes, model years and comfort, but the reality is its junior hockey’s horse-and-buggy and a necessity to covering the distance between cities and towns in any one season.

The amount of time on the bus can vary, of course, mainly due to geography and the location of one junior team to another in the same league, but generally, lengthy bus rides and travel miles start to accrue the deeper a team advances into the spring.

This is especially true for Junior A teams across Canada that are fortunate enough to win their league, progress to regional competition and perhaps on to the RBC Cup, Canada’s National Junior A Championship.

It’s especially in the months of April and May that the odometer starts to tick more frequently, the trips between games become larger and the ability to deal with adverse bus travel is as important as a game’s first goal or a big save with two minutes to go in the third.

Take the South Surrey Eagles and their run to the 1997 Royal Bank Cup final as an example. Back then, with a 17-year-old Scott Gomez as one of their featured players, the Eagles soared back-and-forth between three provincial stops to win the BCHL championship.

Next was a trip to Cranbrook, B.C., for the provincial title, and then on to Fort McMurray, Alta., and a Doyle Cup victory to eventually represent the Pacific Region at the national tournament in Summerside, P.E.I.

In total, they traveled over 10,600 kilometres in the postseason exclusively, with a large chunk of that coming in their final two stops.

“Travel wasn’t really that difficult during the regular season,” admits Mark Holick, who was an assistant coach with the Eagles that season, a team that put on nearly 3,200 km alone in a regional series to northern Alberta that included a 26-hour bus ride.

“That was our first experience with (extended travel). And certainly there was a little adversity with that type of distance, for sure.”

For junior hockey teams there is no avoiding bus travel, especially in the postseason. But how a team physically and mentally deals with the prolonged distances, bus confinement and general tedium does present its challenges.

As a coach, can you develop a magical science to better absorb the miles for your team? Maybe. But sometimes the travel can be so vast and arduous that it would make a long-haul trucker blush, especially since turnaround time is limited and deadlines to complete certain series are short.

In 1997, South Surrey advanced to the pinnacle of Junior A hockey and earned a berth at the Royal Bank Cup. That season – like this year – the site of the tournament was Summerside and it meant the Eagles needed to board a plane to travel another 4,359 km to get there as the Pacific reps.

“It was literally coast to coast,” said Holick, whose club lost in the final that season to the host Summerside Western Capitals before claiming the national title the following season with Holick as head coach.

Even the misconception that airline travel can somehow ease the difficulty in closing the distance between the two oceans was not lost on the Eagles, who traveled on two separate flights to get to Summerside under tight time constraints.

“It’s a long day with a four-hour time change,” said Holick, now the head coach of the Western Hockey League’s Prince George Cougars.

Despite the rigors of bus – and sometimes airline travel – in junior hockey, there is a positive and seemingly attractive side to the long hours spent on the road.

“Travel is a necessary evil,” says Jason Tatarnic, the eight-year head coach of the Woodstock Slammers of the Maritime Hockey League, whose club put on over 10,000 km last season during their playoff run to the RBC Cup in Humboldt, Sask.

“As you travel you have those times when you look out the window of the bus and wonder ‘how much longer can I do this?’ ”

However, he also admits the time together on the bus can be advantageous to strengthening areas within your group like team-building and camaraderie.

“For me as a coach, the conversations you have with your team and some of the story telling that goes on gives you a good memory of when you played the game. It hasn’t changed much since then. It’s the one constant.”

And while DVD players and personal hand-held devices have aided in passing the time on the bus, the standard game of cards, reading a book or sleeping are still common activities among the players and coaches as the wheels rotate along the highway.

Now, some of the travel hardships can be alleviated by breaking certain trips up, according to Tatarnic. For instance, his team will always have a pre-game meal together en route to road games that are considered long trips.

Moreover, they’ll even go as far as splitting the trip up over an extra day just so the time on the bus is lessened and the probability of “bus legs” abated.

“Especially when you’re on a three-game road trip there’s going to be some fatigue on your legs,” says Tatarnic. “Scientifically it’s proven. The best thing for players to do is stretch and get into their routine as quick as possible once you get off the bus.”

Part of that routine might even include a fun evening on the road with a team function like bowling or helping to ensure the players get a solid night’s rest. In this case, limiting the number of players per hotel room on the road can serve as a definite benefit to the team overall.

But because those small luxuries in junior hockey would require extra costs, not every one of the 127 teams in the 10 Junior A leagues would be able to consume that financial hit.

Either way, tough travel in junior hockey – especially via the bus – is as much a part of the game as a stick and puck. How it’s managed is up to the individual teams.

For more information: |

- <

- >