Schedule

Team Canada (Men)

IIHF World Junior Championship | Dec. 26, 2024-Jan. 5, 2025

Spengler Cup | Dec. 26-31, 2024

4 Nations Face-Off | Feb 12-20, 2025

IIHF U18 World Championship | April 23-May 3, 2025

IIHF World Championship | May 9-25, 2025

U17 World Challenge | Nov. 3-9, 2024

Hlinka Gretzky Cup | Aug. 5-10, 2024

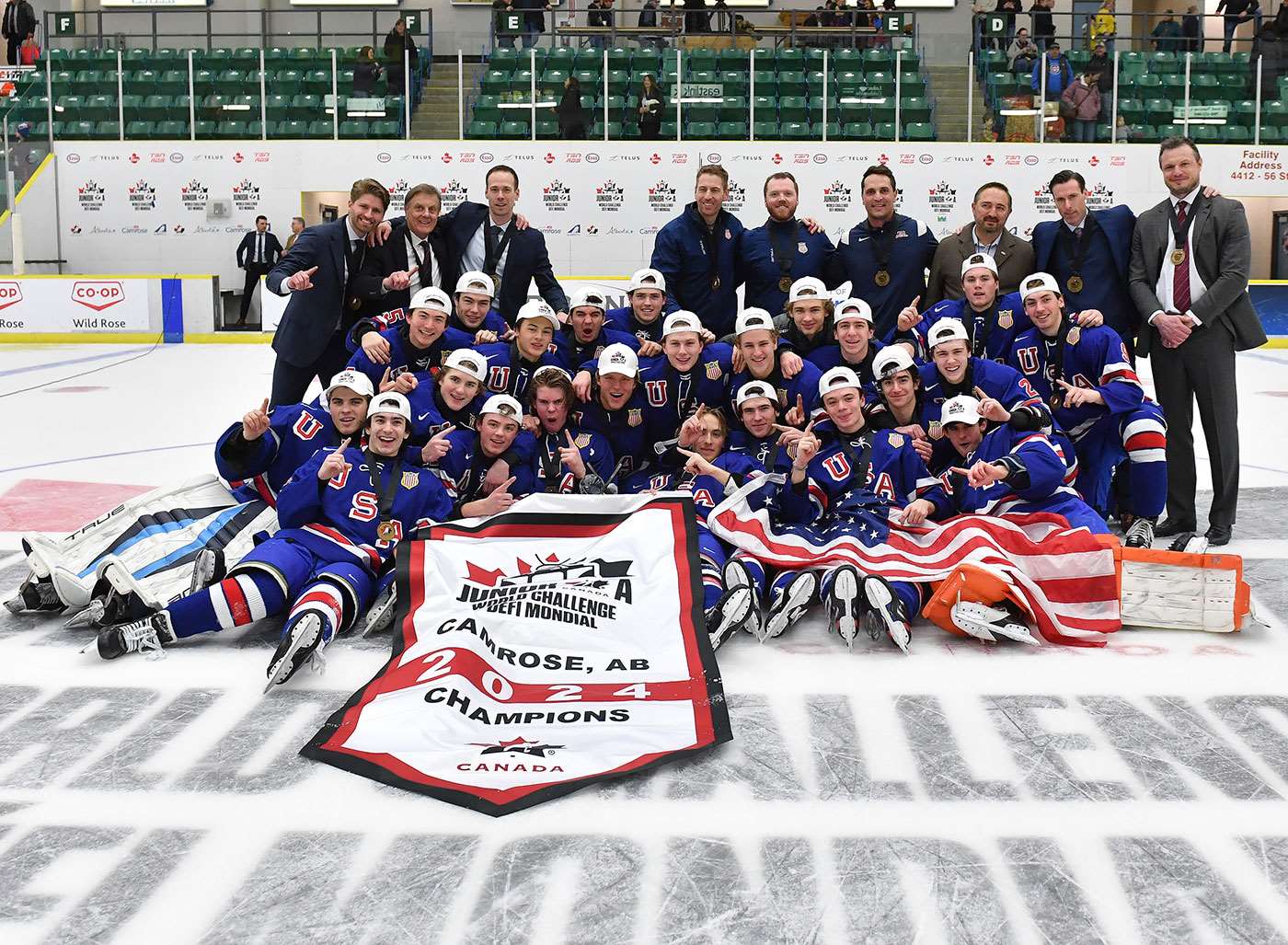

Junior A World Challenge | Dec. 9-15, 2024

National Junior Team vs. USPORTS | Dec 12-13, 2024

Search

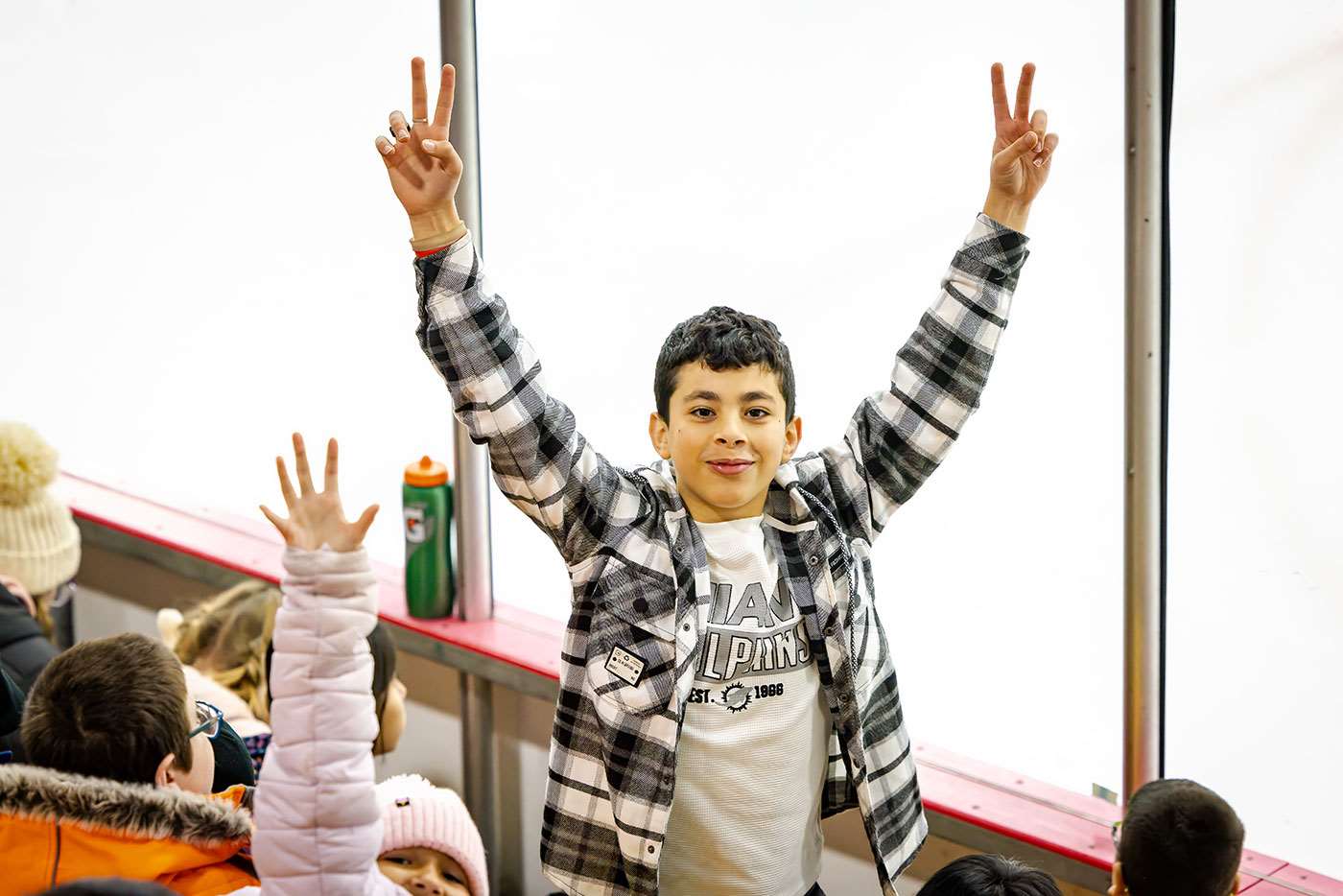

First Shift sparks interest in para hockey

With an accessible and affordable way to try the sport, the NHL/NHLPA program is helping to introduce young players to para hockey and inspire Paralympic dreams

With the NHL/NHLPA First Shift successfully offering a low-cost entry into hockey for families new to the sport, Maxime Gagnon saw an opportunity to expand the program by offering para hockey.

Along with Parahockey Montréal, Gagnon helped to run the program’s first para-specific event in 2018.

“When we started the program four years ago, we started with 15 new players. That’s amazing in para hockey,” says Gagnon, who is the CEO of Parahockey Montréal. “Normally, we receive [across] all divisions about 10 players, not more than that. But for only junior, 15 players, that’s amazing.”

Gagnon is currently hosting the third edition of the NHL/NHLPA First Shift para program in Montreal. One new addition this year was the para program and a First Shift for stand-up hockey had its Bauer equipment fittings back-to-back, which helped to drive home the message that every participant is partaking in the same program.

“The inclusion for me is very important,” Gagnon says. “We’re going to do probably one or two practices all together on the ice, the stand-up and the [para] hockey program.”

Along with equipment, participants will have six on-ice sessions to learn the basics of the game and have fun with their peers. Instructors will help to teach and mentor participants, something Paralympic Hockey Team forward Anton Jacobs-Webb found very important when he started playing para hockey.

Jacobs-Webb looked to veteran para hockey players like Hervé Lord and Ben Delaney to help teach him how to stick-handle and have control of his sled when he was starting out.

“That’s the biggest thing for me is having people mentor you and to show you the little tricks and little tips because there’s so many [skills to develop] to get into [para hockey] because there’s such a steep learning curve right at the beginning,” Jacobs-Webb says.

The timing of this season’s program also aligns with the 2022 Paralympic Winter Games in Beijing, which allows the young participants to see the sport on an international stage while they are trying it for themselves at home. Gagnon is planning to work the Paralympics into the NHL/NHLPA First Shift program, including filming a video to send good-luck messages to Canada’s Paralympic Hockey Team.

Overall, with the combination of the NHL/NHLPA First Shift para program and the exposure of the sport’s top athletes competing in Beijing, the goal is to help spur the dreams of young athletes in para hockey.

“The more accessible it is, the more people will try it. And just more importantly, know it exists,” says Greg Westlake, a veteran forward on Canada’s Paralympic Hockey Team.

“I heard about this sport at the age of 14 years old. I wish I heard about it when I was five. I think that the efforts that we’re doing right now, through programs like [NHL/NHLPA First Shift], that’s what’s going to make the difference for the next little kid born with a disability that can get out there and get in a sled at five years old and really start that [Paralympic] dream so much earlier.”

Thanks to the NHL/NHLPA First Shift, there is an accessible, affordable, safe and fun way to introduce kids to the sport of para hockey across Canada. Gagnon has already seen the benefits of the para program in terms of the retention and growth of the sport at the grassroots in Montreal.

“Next year, we’re going to have the kids who started four years ago with the [NHL/NHLPA First Shift] and they’re going to be invited to the provincial selection for [para hockey] in Quebec,” Gagnon says. “For us, it’s very important. The wheels are turning. The more kids we have, the more players we’re going to bring to the national team or represent our province.”

For more information: |

- <

- >

It’s no coincidence that wherever Assinck has gone in her life, women’s

para hockey has grown with her guidance and support. Inspired by wanting to

learn more about spina bifida, she attended Brock University to pursue a

neuroscience degree. As she completed her undergraduate degree, she played

with the Niagara Thunderbirds and volunteered with the Brock Niagara

Penguins, a sporting program for youth and young adults with a physical

disability.

It’s no coincidence that wherever Assinck has gone in her life, women’s

para hockey has grown with her guidance and support. Inspired by wanting to

learn more about spina bifida, she attended Brock University to pursue a

neuroscience degree. As she completed her undergraduate degree, she played

with the Niagara Thunderbirds and volunteered with the Brock Niagara

Penguins, a sporting program for youth and young adults with a physical

disability.